Second Day

What's AI Got To Do With It?

There have been some really good first of the year blog posts already—from extoling the virtues of blogging, to an appeal to build smaller.

I was a little busy hiking in the rain with my family during the first day of 2026 and building forts and playing fairies with my daughter in the evening, so I didn't get a chance to ponder on the time ahead, but hey, nothing wrong with being second.

Just Semantics

Okay, so the subtitle to my post carries a lot of weight, and I deliberated whether to include it or not.

One major part around the trepidation is specifically in how charged and almost meaningless the term "AI" has become.

This is quite unfortunate, though I do think it is deliberate. The fuzzier the term remains, the easier it is to muddle through some of the thorny issues around it.

On Mastodon, xgranade wrote about this in a thread that echoes a lot of my thinking.

The trouble is that the term "AI" is a marketing term and not a technical term, and as such can always be retroactively redefined in a way that dodges criticisms.

And also:

It's hard as shit to talk about this because there's so much disinformation and intentional confusion out there.

Yeah, exactly.

My fourth quarter of last year meandered along these lines, starting with a sort of experimental conference talk, followed by a one, two, three blog post follow-up streak.

This surprised me, because I really didn't think that I'd be that guy who would be writing about this, like I'm obsessed or something... and yet...

The third of those posts tries to sidestep the quagmire of etymological confusion by substituting "AI" with The Industry, which, in my mind, is a good-enough substitution, though not perfect.

Years ago, Martin Fowler wrote about semantic diffusion back in 2006, describing something that happens (in this case within the sphere of tech jargon) that causes terms to lose any sort of usefulness.

That idea rears its head pretty often in these topics.

This isn't even something that plagues the AI skeptic crowd (speaking of semantic diffusion).

Dexter Horthy, founder and CEO of HumanLayer, recently delivered a talk explaining how AI coding tools can be used to "solve hard problems in complex codebases".

In his talk, he insists that Spec Driven Development has lost meaning, and as a result, tries to recontextualize (pun intended) his approach as a subset of context engineering.

We come up with a good term with a good definition and then everybody gets excited and everybody starts meaning it to mean 100 different things to 100 different people... and it becomes useless.

I agree.

The same has happened with AI at large, though I think there is a slight distinction with respect to Fowler's initial definition of semantic diffusion. He writes:

Semantic diffusion occurs when you have a word that is coined by a person or group, often with a pretty good definition, but then gets spread through the wider community in a way that weakens that definition. [Emphasis mine]

I don't think Artificial Intelligence was ever a pretty good definition.

Unless, of course, you are a megacorporation that needs public buy-in for an endgame that is horrifyingly anti-worker at best, and eugenicist at... baseline.

Anyway, it's of little surprise, then, that as I reflect on the year to come, I bet I'll be talking/writing about this topic some more.

If you've read my prior writing on this subject and have neatly filed me away into a semi-useful term like AI skeptic or hater—I invite you to stick around for a moment.

When we start from the foundation of polarization, it is very unlikely that we can work together for a better future.

Permission

We may have crossed a line, at least in public perception, that any megacorporation with the power to do so can pillage the Internet for content without any form of consent.

This is a tragedy.

But even if the public perception is tepid, the effect on creators can be devastating.

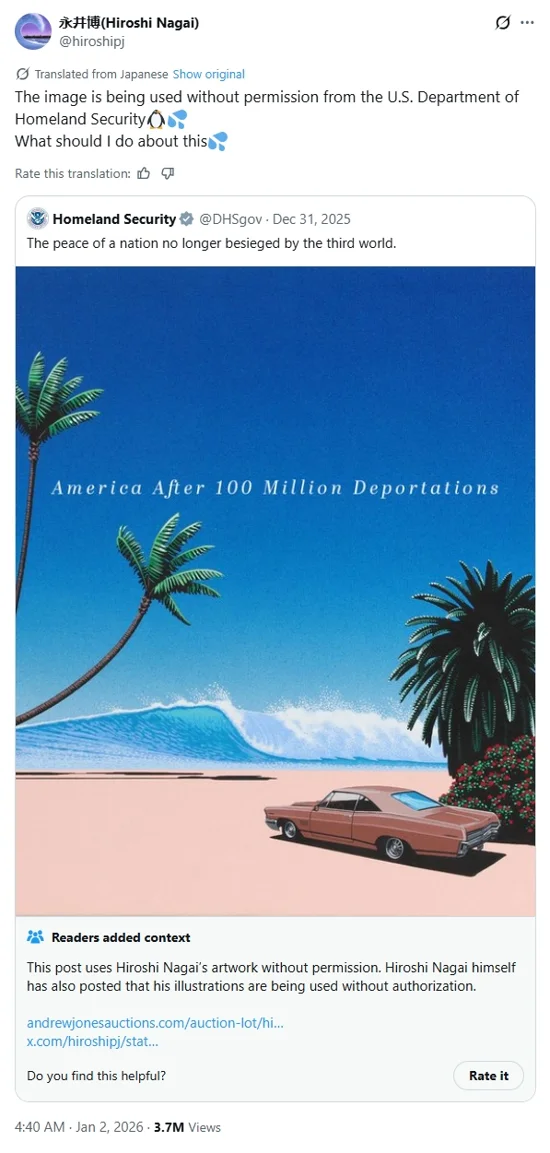

Think about this post from the US Department of Homeland Security, where they display an image, emblazoned with their xenophobic agenda:

Notice that the Japanese artist Hiroshi Nagai is enraged by its usage. This is insanity.

Consent matters.

Then, let's juxtapose this situation with the deplorable news that came out today about Grok AI producing sexualized images of minors.

This is only possible through the extrapolation of data without permission or consent, and it is being used in a manner that feeds the fantasies of these demented oligarchs.

Maybe the similarities are not obvious. And maybe my connection is a little far-fetched.

But it is not impossible to draw a line between content theft by tech companies into harmful and destructive content served up to consumers.

Accountability

What's even more disgusting with the Grok situation is that, so far, there is a complete lack of accountability, save an "apology" from Grok itself.

(Wow, it's only January 2, and there is already way too much to write about.)

A few days ago, Satya Nadella (CEO at Microsoft) started a blog. His first post looks ahead at 2026 and focuses on... well, did you think it wasn't going to be AI?

"We have moved past the initial phase of discovery and are entering a phase of widespread diffusion," he writes.

He then lists a few bullet points in terms of what is yet to be figured out.

And lastly, we need to make deliberate choices on how we diffuse this technology in the world as a solution to the challenges of people and planet. For AI to have societal permission it must have real world eval impact. The choices we make about where we apply our scarce energy, compute, and talent resources will matter. This is the socio-technical issue we need to build consensus around. [Emphasis mine]

What does he mean by "societal permission"?

Does he mean in terms of production or consumption?

You see, the terminology used here is useless.

Are we talking about "societal permission" for the disturbing Grok outputs linked above or its disturbingly problematic AI girlfriend feature?

Or is it only for the so called "agents" discussed in Horthy's video?

Hopefully this highlights the problem here, but it still leaves open the question of consent and accountability.

Such A Tool

I lived in an time when calling someone a "tool" was considered a pejorative. (I'm an old.) Maybe it was meant to say that you, as a person, have no agency.

Now, I'm seeing the terminology shifting from "using AI" to "it's just a tool."

I presume this is in order to shift responsibility back into the hands of the user. Giving us back some sort agency. This is good, right?

I can see where this is helpful terminology in the world of software development. Even if the engineer uses "AI tools" for their work, they are responsible for any lines of code that they commit.

This, to me, feels like a slippery slope. Maybe careful usage means that the engineer is adequately confident that no laws were broken in the generation of this content.

However, I would be very wary of accepting full accountability for anything generated by an LLM.

Late last year (feels weird saying that), a German court rejected an argument made by OpenAI that users of ChatGPT should be legally liable for generated content. As noted in an article about this on The Guardian:

Because its output is generated by users of the chatbot via their prompts, OpenAI said, they were the ones who should be held legally liable for it – an argument rejected by the court.

Thankfully, the courts rejected this notion.

But I hope I don't need to convince you that this is extremely scary.

Corporations will go through great lengths to shit on their users.

Analogy

I have one more analogy before I conclude this piece here.

In the US, gun rights advocates often use the phrase "guns don't kill people... people kill people."

They are the same kinds of individuals that might look at a firearm as a tool, something that is used by a responsible gun owner.

The way that it is used is what matters. And therefore, gun manufacturers should not be impeded from creating more guns, and individuals should not be restricted from owning them.

I admit, I am not well-versed in gun rights arguments. I don't own one, nor would ever want to own one.

But I know plenty of folks who feel differently.

They feel confident in their usage of guns, in the right circumstance. And I'm okay with that.

However, I still think the gun industry should be heavily regulated, and I do think that manufacturers should be held accountable for risks incurred by users and victims of gun violence.

I believe there are gun owners that also agree with the above statement.

Conclusion

There's a funny response to the Grok incident over on Mastodon by user Brian Tatosky.

While I think this is genuinely funny, it still relies on the idea that Grok is a tool much in the same vein as Excel.

I think it's a bit more complicated than that.

But I do think it's a good start—ensuring that companies can't weasel their way out of accountability.

Adriana Tan has done actual, tangible work that serves as a good place to start.

She advocated for California's AB 316, which states:

This bill would prohibit a defendant who developed, modified, or used artificial intelligence, as defined, from asserting a defense that the artificial intelligence autonomously caused the harm to the plaintiff.

Yes! We need more of this.

And, whether you are a user of these tools, or someone who is infuriated by them, we still need to rely on each other to ensure the big tech companies cannot continue washing their hands of the many existing abuses within the AI industry.

Perhaps you are aware of how David Sachs, the White House's so-called AI and crypto czar, is working to undermine laws like California's AB 316.

He is behind the White House's latest effort to eliminate the efficacy of state laws aimed at regulating the AI industry.

There are already over 100+ state-level laws around AI safety, from mitigating mental health risks to minimizing the effect of deepfakes, and so on.

All this is in jeopardy.

Last month, the On the Media podcast released an excellent episode titled Deep Fakes, Data Centers, and AI Slop — Are We Cooked?

Host Brooke Gladstone cited a Gallup poll from September that claims 80% of US adults want the government to prioritize AI safety rules.

On the show, Gladstone interviews Stephen Witt, author of The Thinking Machine. They discuss power usage, resource consumption, and effects on the economy.

While he remains somewhat bullish that AI technology will survive the impending bubble pop, he still contemplates on how to combat the monopolistic and unrestricted tactics used by big tech.

I just don't know how you stop it. I guess the way to stop it is very aggressive antitrust action against one of these companies or all of them, breaking them into smaller companies and putting it subject to some sort of consumer regulatory board. The status quo today is very far away from that. Of course, anything can happen, but you just need the political will from average citizens to organize to make that real. I think we're far away from that right now.

We need the political will from average citizens.

This can happen, but it won't if the big tech companies continue to control the narrative.

I guess that's why I think I'll continue to write about this. Whether you think I'm an AI hater or an old man yelling at the cloud—even if you think I'm a tool. 🔧

What's the worst that could happen if I'm wrong? Well, you'll keep using your AI tools, costs for usage, inference, and datacenters will stabilize, our planet will keep inching toward "too hot", just as it has been.

But what if it goes the other way? Are we going to be asking ourselves, "what harms could we have prevented," and wishing ourselves "thoughts and prayers"?

From Nadella's blog, referenced earlier, he states, "Ultimately, the most meaningful measure of progress is the outcomes for each of us."

Who is the us, here? Are you including the people that have already been harmed?

I'm sorry, but in this case, the ends do not justify the means.

You can keep your Machiavellian, transhumanist visions of the future to yourself.