Metaphors

Similes are like metaphors that lack commitment.

Analogies are metaphors that over-extend their welcome.

I still like using them, though. Writing is much less fun without them.

It's not that analogies prove anything. They can easily be deflected or turned on their head. In fact, they can often stifle discussion or distract from the issues at hand.

But still, they're sometimes useful as a shorthand for parallel comparisons. The hope is that they will help clarify complex subjects, or enable a better understanding of a particular topic.

In this post, I'll be on both sides of that fence.

Purpose

In the past, I've tried to create a distinction in my writing between "AI" tooling and "AI" industry. Even though those two things are conjoined, I've tried to adapt my language to be more precise about what it is that I am critiquing.

On this blog, it was largely set off by a question on Mastodon, asking if the general consensus on that platform is "massively against AI."

I did attempt to answer in good faith, all while explaining why I thought that "language matters."

That thread died down a couple of months ago, but of course I'm still thinking about it.

If that weren't the case, I probably wouldn't have spent so much time editing this sentence! 😅

Looming over this whole topic is the term "artificial intelligence," which itself is a very flawed metaphor.

I'm hardly a scientist, neurologist, educator, or philosopher to argue why that is—but needless to say, I've yet to find consensus on a singular definition of human intelligence.

This should raise some very important questions.

Is intelligence memory? Recall? Problem solving? Emotional awareness? Adaptability? Creativity? Self-awareness? Novelty? Ingenuity? All of the above? And how is it measured?

What is "artificial" intelligence aspiring to be? Who is deciding what intelligence looks like? Why do we trust that we are headed in the right direction?

Narrow

Those broad questions certainly feel like scope creep for a simple-minded blogger such as myself. So I will try to narrow my focus.

But even within a proper distinction between "tools" and "industry," I feel an additional need for precision.

For example, within the "tooling" alone, I could write about image classifiers, topical recommendation engines, statistical learning methods, generative pre-trained transformers, translations, transcriptions, and so on (I understand some of these overlap).

Each of those are complex in their own way and could command a wide discussion even on a very narrow topic.

For the sake of brevity (yes, this is a little tongue-in-cheek), I want to focus on the anthropomorphism of "chatbots."

Anthropomorphism

Last year, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) released a paper titled The benefits and dangers of anthropomorphic conversational agents

The Abstract poses:

When users cannot tell the difference between human interlocutors and AI systems, threats emerge of deception, manipulation, and disinformation at scale. We suggest that we must engage with anthropomorphic agents across design and development, deployment and use, and regulation and policy-making.

The paper points to the dangers of potential subterfuge when dealing with LLM-based systems that are built to mimic human communication.

This got me thinking about how best to represent these systems.

So here's a thought experiment (ooh, an analogy!)...

Let's say you've been suffering from some health ailment, and you meet someone who is a doctor. You tell her your symptoms, and she provides you with some guidance, but instead of giving you a diagnosis on the spot, she advises you to consult your primary care physician (because this is generally what a doctor might do). That's a little frustrating because you don't get an immediate answer, but you appreciate their time.

Or, alternatively, let's say a doctor hears your symptoms, and then promptly diagnoses you on the spot. You think to yourself, "Wow! That was fast. I'm glad I asked him." Then, you go and ask someone else what they think of the doctor, and they tell you, "Well, he's actually an actor who's been playing a doctor on TV for several years now. There's a fair chance he may have misdiagnosed you."

In this particular scenario, you may be able to confront a human who gave you wrong information. You could, to some degree, hold them accountable.

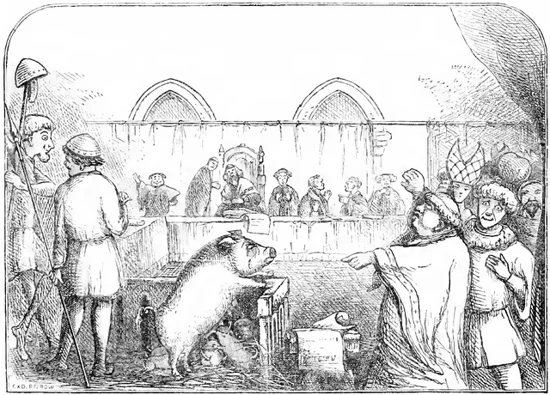

Trial of a sow and pigs at Lavegny, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons

Trial of a sow and pigs at Lavegny, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons

Not so with text predictive systems. They are built to mimic human thought, but they certainly won't be held accountable.

Either way, I hope you agree that it's important for the second "doctor" to properly identify himself.

In the publication FAccT '24: Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, there is a paper titled From "AI" to Probabilistic Automation: How Does Anthropomorphization of Technical Systems Descriptions Influence Trust?.

The researchers found that anthropomorphism influenced different groups in specific ways, often leading to higher levels of trust and over-reliance on systems with anthropomorphized descriptions.

Whether this is problematic in the context of describing text synthesizers is an important topic.

Maybe the metaphors are helpful to consumers. They do, after all, provide a quick way to explain a system's general purpose ("chat agent") and capabilities ("coding assistant").

But, the opposite is also true. Using language to ensure trust in unproven systems is certainly an exploitable reality, and the advertising and branding of unregulated tech companies can sometimes resembled propaganda.

Tech companies and venture capitalists are not interested in precision. They are interested in anything that will drive their valuation upward—overstating and overpromising is part of the business plan.

This is a problematic reality for consumers. This is even without pointing out the implications on mental health, and the multiple lawsuits related to suicides.

For many of us technologists, we might be able to see through the illusion. We may feel insulated from the dangers.

But that's not really a given.

More Subtle

But even more subtle than that, there are ways that language steers our thinking.

Notice in my analogy above how the gender of the doctor changes. Did you notice it? If so, how did you feel about what the examples represent?

As a corollary, it's been pointed out that many of the "assistant AI chatbots" tend to be gendered as female (whether by voice or name), whereas "coding assistants" generally tend to have male-centric names.

This isn't by chance.

Additionally, due to implicit bias in the training sets, the outputs generated by these complex predictive text systems will always skew toward the disappointingly biased status quo.

Moreover, a recent John Hopkins study finds that these generative systems are creating a rift between English and other languages.

Rather than leveling the playing field, popular large language model tools are actually building "information cocoons," the researchers say in findings presented at the 2025 Annual Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics earlier this year.

The study finds that generated content related to international affairs is extremely biased, and American perspectives are being pushed to users that are already marginalized and exploited.

Most of my readers will agree that consolidated power over these kinds of technologies poses a substantial risk and very real harm to communities that are already vulnerable.

Yet, some of my readers may disagree on what action, if any, we as technologists should take in lieu of the very real, very much consolidated power in the hands of very dangerous people.

Perhaps the answer is closing the door. Or maybe the answer is more openness. Or maybe it's something else.

Unfortunately (or maybe fortunately), that's not the particular rabbit hole I'm chasing today.

One Last Analogy

I'm zooming out again to look at this from the industry perspective.

We've ceded a lot of control of the messaging to the tech companies, and this has led to public misconceptions about the capabilities and dangers that these systems pose.

I've already used this analogy, but I'm going back to it for a bit.

Gun manufacturers, lobbyists, and interest groups have long dominated the conversation about how to (not) regulate firearms. By controlling the language and exclusively focusing on Second Amendment rights, they kill any legislative pressure to regulate and control their industry.

It is my opinion that this has led to catastrophic events, particularly in the United States.

But this is hardly the only industry that abuses legislative power.

Oil and banking are just two examples that come to mind.

They leverage their weight in order to prod at rules and regulations that are meant to protect citizens.

In his latest piece, political commentator Matt Stoller writes about the monopolistic practices of greedy bankers and their competing interests with cryptocurrency peddlers.

In his piece, he outlines how those competing interests killed a terrible piece of legislation called the Clarity Act, which would have removed regulations protecting against speculation and market manipulation.

Avarice (Avaritia), from the series The Seven Deadly Sins, CC0 1.0

Avarice (Avaritia), from the series The Seven Deadly Sins, CC0 1.0

Somewhat fortunate for consumers, the greedy bankers killed a deal that would have enabled exploitative crypto scammers.

"This battle is one where there is no good guy," writes Stoller.

It's unfortunate that we have these two interest groups as the last line of defense protecting consumer rights. It would be great if there were a third option.

But for now, the fact that crypto finally got stopped, at least temporarily, by the banking lobby, well at least it’s funny. And it does show how checks and balances are useful even when everyone involved is deeply flawed.

And maybe it's the same with "AI" technologies.

Who knows what will come of Elon Musk's lawsuit against OpenAI. But hopefully it does provide us with some breathing room to seek a better alternative.

Forward

There is a bit of optimism in a few of the voices I follow, most presciently Cory Doctorow, particularly with his latest writeup for the Guardian where he again discusses the tech giants' obsession with reverse centaurs.

Maybe there is a way forward through the rubble.

But in the meantime, I'm still interested in how we can zoom in and out from these issues that are already known and documented.

If we know about these systems and how they operate, how can we help inform others? Is there anything we can do to make others safe? What kinds of decisions can I make that would move the needle in one direction or the other?

It may be that you feel helpless, because all of it feels so inevitable.

As Doctorow points out:

“There is no alternative” is a cheap rhetorical slight. It’s a demand dressed up as an observation. “There is no alternative” means: “stop trying to think of an alternative.”

Language matters.

The tech companies want you to adopt the vernacular of their marketing because it helps create a perception that these systems can be trusted.

Dr. Emily Bender and Nanna Inie write about how we can change the way we speak.

A more deliberate and thoughtful way forward is to talk about “AI” systems in terms of what we use systems to do, often specifying input and/or output. That is, talk about functionalities that serve our purposes, rather than “capabilities” of the system.

It takes effort to do this.

But whether you're using these tools or not, you can still abstain from being complicit in the coercion being pushed on the population at large.

I'll end on a metaphor... or rather, a synecdoche.

Don't be a mouthpiece.