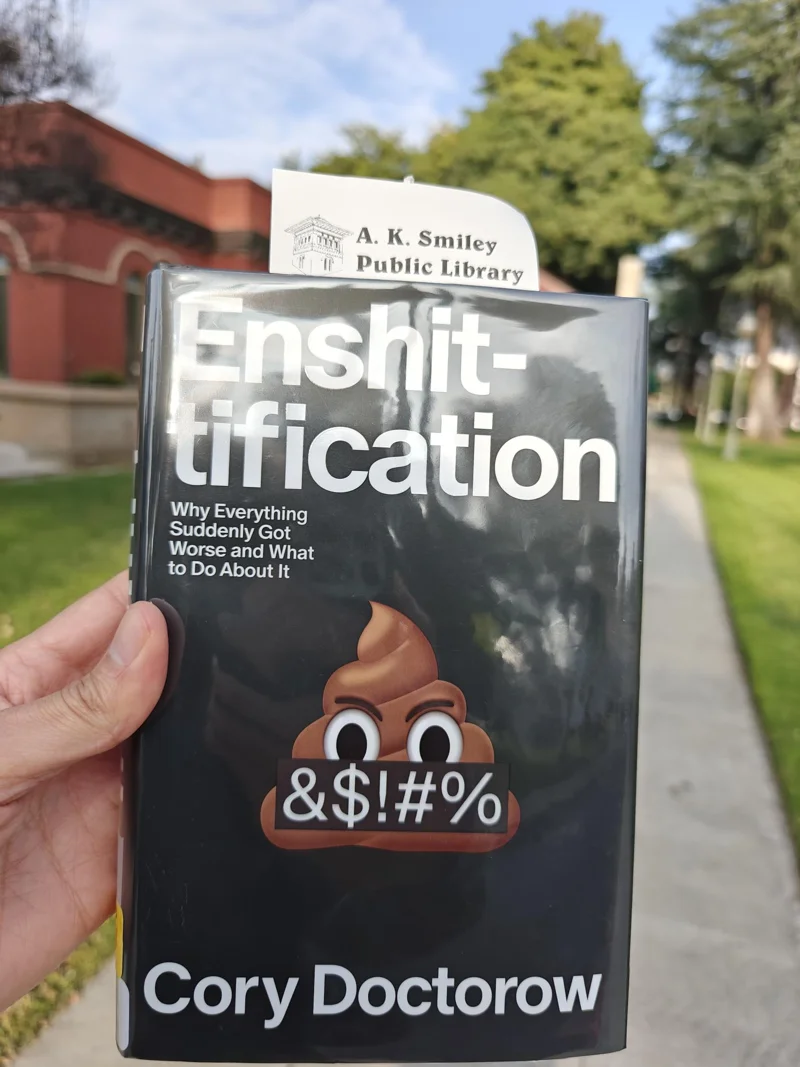

If you've followed any of Cory Doctorow's recent discourse on enshittification, it should come as no surprise to learn of the devious machinations employed by monopolistic companies.

As Doctorow points out in his aptly titled book, Enshittification, asking why companies go down the path of screwing over their users and their customers is the wrong question.

The real question is, why wouldn't they?

"They would like to pay the lowest-possible wages, offer the lowest-possible quality, and sell at the highest price they can name," Doctorow writes. "... which means companies start to enshittify when they can."

Deterrents

There are a few deterrents that keep companies honest, according to Doctorow.

Competition, regulation, interoperability, and solidarity (collective worker power).

When possible, monopolistic companies are keen to strong-arm any up and coming competitors, either by buying them outright, or bullying them out of the business.

At that point, they can easily collude with the remaining monopolistic competitors in order to avoid regulation and bypass accountability.

In order to lock in users, these companies make interoperability nearly impossible through walled gardens or DRM tricks.

And ultimately, they devalue any leverage workers may have to oppose their depraved goals.

These are short, euphemistic descriptions of the rapacious and malignant tactics employed by all the companies we've come to depend on: Microsoft, Alphabet, Meta, Apple, Amazon, and so on.

Additionally, without effective regulation, companies are incentivized to follow the same shitty patterns laid out in the past.

You know, like when IBM spent 13 years (!) litigating a suit (one of several over the span of 20 years) accusing it of being a monopoly.

That has served as a template for many of the patterns tech companies continue to follow.

The audaciousness gets lost in these snippets, so I'd encourage you to read Enshittification or pretty much any other book that looks at the inner workings of our techno-feudalist landscape to get a better sense of the scale and depravity.

It's sometimes darkly comic, like when you read about how someone was able to collect and sell urine disposed by Amazon drivers—on the Amazon platform!

But time and time again, for the past several decades, these companies have laughed off attempts at regulation, and continued to cut corners at the expense of their users and customers.

They are so bold and uncaring that recently, they've had no issue showing that their real allegiance is only to each other.

Remember that fascist tech dinner—a real who's who of billionaire assholes? Or how OpenAI's president is a Trump mega-donor? Or how about that propaganda film screening on January 24—you know, as if nothing else was going on that day (no, I'm not talking about my birthday either).

Shift

I recently read JA Westenberg's post, The Discourse is a Distributed Denial-of-Service Attack, likening the unfettered firehose of current media discourse to a DDoS attack on our cognitive functions.

It's not that discourse itself is unimportant, they argue, but rather that "the structure of the discourse prevents us from thinking well about even the most important topics"

Westenberg suggests taking a step back from a given subject—to take time to learn more about it, to seek out the gaps in your own judgment, and to think about what might change your mind about your predisposed positions.

This is great advice.

A bit of self-reflection here leads me to believe that I, too, am part of this problem.

There are already an absurd amount of hot takes about my most recent subject of interest.

I am led, however, to this somewhat paradoxical point of stepping back, but also kind of leaning in a little.

So here's my caveat.

I believe that the process of writing, specifically long-form, can also be an opportunity to explore my own thinking, expose certain logical gaps, and search for expertise in areas I am not as familiar with.

That's My Prompt

This is all setup for my actual topic here, so if you have enough to chew on, and would rather not stick around for the punchline, no hard feelings.

I fully endorse the aforementioned stepping back.

But for those of you reading further, this is where I explore the eventual and inevitable enshittification of "AI" platforms and some thoughts thereof.

As a primer, here is the Natural History of enshittification, according to Doctorow.

- Platforms are good to their users.

- Platforms abuse users to make things better for business customers.

- Platforms abuse business customers clawing back all value for themselves.

- 🏆💩🏆

Where We Are

If you don't believe that "AI" services will be another exhibit in the museum of the Enshittocene Age, then I both applaud and envy your optimism.

It's hard to say whether we are (or ever were) in the first stage of enshittification. (Is "AI" being good to the users?)

I'm not here to argue or to discredit the personal accounts of software engineers or other professionals who have modified their work to take advantage of new workflows made possible through the new tooling.

But an argument I've made in the past is that "AI" is not merely the one thing you've found success (or failure) using.

Instead, it is a multi-tentacled monstrosity that is flinging itself in every which way.

And while one of those tentacles might propel you forward in some particular direction, many more are simultaneously wreaking havoc in other sectors.

In a blog post last week, Sarah Friar (CFO, OpenAI) claimed that "our job is to close the distance between where intelligence is advancing and how individuals, companies, and countries actually adopt and use it." (The "it" in question is the ChatGPT tool.)

In other words, they are positioning themselves as the middlemen (intermediaries) between human intelligence and ... everything?

It's hard to understand precisely what she means in that statement. In the previous paragraph, she's talking about ChatGPT as a singular "tool for curiosity" that somehow becomes "infrastructure" for pretty much everything that people do—"create more, decide faster, and operate at a higher level."

Then she positions ChatGPT as the catalyst of what makes the world go round.

Whatever the case is, by positioning OpenAI as the intermediary, it's as if they are copy/pasting a recipe for enshittification directly out of Doctorow's book.

Even if the "singular tool" narrative is one that you follow, and you agree that it is a tool that is currently "good to its users,"it's hard to deny the lengths these companies are going to in order to coax business customers.

The rebrand of Office365 to 365 Copilot is almost a farcical example of this.

Three And Six

Whether by legitimate usefulness or brute force, the ubiquity of services controlled by these tech companies is reaching critical mass. The stage is set.

So the next thing to keep an eye on, then, would be to see who the major players are in this space.

In Enshittification, Doctorow explains what happens in a market dominated by a small number of enterprises.

In a sector where true competition exists, there may be hundreds of competing services, creating a sort of "collective action problem".

It becomes impossible for all these competing entities to screw over customers (price-fixing) or to collude in order to eschew legislation (lying to regulators).

But when a sector dwindles to five companies—or four, or three, or two, or just one—the collective action problem is annihilated by the inevitable coziness among the executives of the incestuous industries.

This exact dilemma is developing in front of us in plain sight.

Dario Amodei (CEO, Anthropic), on the Cheeky Pint podcast back in August was asked about the current "market structure" and whether we'd be seeing newer upstarts with specific use cases (you know, competition).

It's very hard, it's hard to tell for sure, and I think there was quite a lot of uncertainty two or three years ago. But I think we might be relatively close to the final set of players, if not necessarily the final market structure or the roles of the players. I would say there's probably somewhere between three and six players, depending on how you count, and those are the players that are capable of building frontier models and have enough capital to plausibly bootstrap themselves. [Emphasis mine]

You don't have to look far to find incestuous dealings between all these companies.

Remember how antitrust court documents show that Google pays Apple $20 billion for the honor of being the default search engine in Safari?

It's the same with those ouroboros-like "AI" investment deals you read about, and that's just the stuff we know about.

What this will mean in the long term is that any competing services to the big three or six players (depending how you count), will likely need to go through the big three (or six).

It's a losing proposition, especially once market dominance is asserted and users are hooked due to powerful network effects and business mandates—at which point, resistance becomes nearly futile.

Open Door Policy

One of the means of battling monopolies is through healthy competition.

I believe this is why some proponents of these systems wish for a more open environment.

The hope is that by "democratizing" the technology, we can fight back against "centralization."

At every point where corporations have tried to control "open source code," there has been an answer, typically through licensing, which attempts to break out of said dark patterns.

(See GPLv3 and Tivoization, as well as AGPL and the SaaS loophole.)

It is pretty clear that open systems do provide a competitive threat to closed systems, otherwise companies wouldn't be trying so hard to enclose the code.

You can see this play out with how Europe is trying to break out of its dependence on US-based closed platforms.

Open-source is both the fuel and foil of these closed systems.

But I don't see licensing as a way of achieving any sort of control and sovereignty over the commons, specifically in this sector.

The holy grail here would mean that some sort of legal/licensing fix could make it so that these huge frontier models would not be controlled by the tech companies, but rather by "the commons".

I think this is laughably untenable. The costs alone of training these frontier models are not going to be written off as a cost-of-doing-business by these companies. They will protect that tooth and nail.

All that information you're giving away will eventually be enclosed.

But even if we were to agree as an open-source collective to make our code available for ingestion in exchange for open models, this is blatantly self-serving and myopic, ignoring the harms this causes elsewhere.

These models cannot work without the continued processing of textual and visual data.

You would have to agree with the corporations that devouring work from researchers, scientists, authors, screenwriters, artists, illustrators, poets, and journalists (to name a few) without consent is not only ethical, but also (perhaps more importantly) legal.

Without continual training data, your "AI" chat agents will never evolve. Their basis for "current events" will always be stuck within a crumbling democracy turning itself into fascism.

So no, it's not just about the code.

These companies will continue to gobble up everything in their path.

I wrote recently about Anthropic's investment into the PSF (Python Software Foundation), and how I thought that on the whole, this was probably a positive move for the PSF.

This remains true if the PSF can maintain committed to its mission without unscrupulous dealings and/or undue pressure from Anthropic.

On the other hand, Anthropic's recent purchase of Bun feels a bit more like an old school acquisition.

At face value, it is a win for the developers (who would otherwise be doing their work for $0 in revenue). But on the road to enshittification, it is part of the playbook.

If you squint a little, you can see the parallels with Microsoft's acquisition of GitHub. Once the "good software" got a bad owner, it would only be a matter of time before a downward decline.

Back in December, Microsoft announced that it was going to impose some pricing changes for self-hosted GitHub Actions. It was met with such vocal opposition that the company decided to postpone the change in order to "re-evaluate" the approach.

That was a close one. But I doubt that's the last we've heard of it.

Behind Closed Doors

I must admit, the interplay between open-source code and these frontier models is messy and disruptive, without a clear answer to its legality or ethics.

I am more than willing to admit that I don't have a great handle on it or in which direction it should or could go.

But I maintain that focusing on that aspect alone is inherently dismissive of the greater context we're living in right now.

With "AI" being a many-tentacled marketing term, it is still important to try and understand what is possibly happening behind closed doors.

A couple of days ago, The Tech Oversight Project released a report with unsealed court documents.

The documents provide smoking-gun evidence that Meta, Google, Snap, and TikTok all purposefully designed their social media products to addict children and teens with no regard for known harms to their wellbeing, and how that mass youth addiction was core to the companies’ business models

Some of this stuff is quite sinister. One exhibit of an employee message exchange includes, "Oh my gosh yall IG is a drug," and "Lol, I mean, all social media. We're basically pushers."

I'm not saying regulation like the Kids Online Safety Act is what is needed here. That bill would be ineffective at stopping the large tech companies.

Instead, I'm making a connection between the devious machinations of big tech companies and the likely harm they will cause with "AI" technology which has already been shown to cause harm—both in how it is trained and how it is used.

As another example from the social media side, Doctorow points to Tik-Tok's use of a "heating" tool, which is used by the company to ensure how many views any given video might accrue (anywhere from 5,000 to 5 million).

This allows Tik-Tok to ensure a video's virality of a certain kind of content, which may then drive other creators of similar content to the platform. (FOMO is real.)

What's very cynical about all of this is that when decisions are made by algorithms within an app, it serves to obfuscate any sort of accountability or responsibility on the part of the company.

This is the same logic used by Uber, in effect paying lower wages to desperate drivers based on algorithmic wage discrimination.

It all works based on user surveillance. Each and every single action is monitored and recorded, then turned against users.

Adoption and usage of "AI" services will only increase the datapoints for further "twiddling" by tech companies.

As another example in his newsletter, Doctorow examines how Google will continue exploiting the ad business to even greater lengths with the help of "AI" technologies. They'll be selling "AI"-based "personalized pricing," which is just a euphemism for surveillance pricing.

Similarly, OpenAI is dipping its toes in advertising, and reportedly, they'll only be giving advertisers "high-level" data on ad performance. No need to imagine how badly this could go for both users and business customers.

Again, it bears saying.

If you do not think that these tech companies are using their "AI" apps to monitor and collect data that will then be used against you (and all other future users), I really do envy your trust in these companies.

They have every reason to extract as much value from you, to laugh off every regulatory hurdle, and to ignore any calls for accountability.

How long did it take for Apple and Google to remove Grok from their respective App stores for displaying pornographic CSAM images?

What's that? They still haven't?

And you mean to tell me that there are other apps that pretty much do the same thing?

But surely there's someone who will be held accountable for this, right?

If this level of egregious and distressing behavior is being done in the open—what is the likelihood that these same datapoints are being used and abused in unimaginable ways?

Response

As distressing as all this sounds, it's easy (and defeatist) to remain cynical.

As mentioned above, deterrents exist.

While antitrust regulations (and enforcement) are fundamental to all of this (and there's reason to have some hope there), I've been trying to wrap my head around how I as an individual should or could respond.

I'm also hopeful that others might wrestle with similar introspection.

I truly think it is important to be clear about how we communicate about the technology, both within our discipline and, perhaps more importantly, with those outside of it.

It's not even necessary to lead with a negation (such as "AI is bad"), but rather, with a recognition of how enshittified our world has become. What are some of the causes? What are some of the examples? What do we lose in the process?

By exposing the despicable tendencies of tech leaders and monopolists, we can at least all have a similar starting point.

We aren't anti-technology. We are pro-worker. We want to protect our world, our communities, our homes.

Companies will continue to use dark patterns, making it harder for consumers to differentiate between what is true and what is not.

As technologists, we're often called upon when our family members are having problems with their router or issues with their printer. We may not always like this responsibility, but this is our responsibility nonetheless.

For professionals that are finding usefulness with the new tools, I don't mind reading about your excitement about your newfound approaches to solving problems. I'm curious about the benefits, as well as any gaps that may be exposed.

My only critique comes when the excitement turns to proselytizing.

We don't need to use the language of inevitability or other talking points from the big tech companies.

If you don't know what those talking points are, take time to read their press releases, interview transcripts, and blog posts. Those will generally expose some of their weaknesses, and they'll try to double down to patch them up.

Recent examples of that include Satya Nadella (CEO, Microsoft) and Jensun Huang (CEO, Nvidia) asking people not to say bad things about "AI," or perhaps even more strangely, Nadella warning that we must "do something useful" with "AI."

On a more esoteric level, we shouldn't back down from philosophical or ethical discussions about the usage of content, especially outside of the engineering space.

Should artists/creators have rights to their works? What might a system of consent look like? Are the tech companies within their right to scrape everything on the web?

As individuals, we don't have a lot of leverage against these monopolistic billionaires. Conscious consumerism alone won't do it.

Our opportunity to push back is in the collective.

If you've chosen to use these tools during the honeymoon period (wherein you feel that the value added by these tools outpaces the harms caused)—then use the tools to create competing, interoperable systems.

Your goal should be to push people away from big tech dependence, not toward it.

I'm not exactly sure what that looks like. It could be pushing people toward open models or local models.

Is the future you're envisioning one that requires developers to pay a monthly fee (or fees) to three or six (depending on how you count) companies in order to stay competitive? Does it require that small/medium employers subsidize subscriptions to these tools?

Some of the commentary I've seen from heavy users is that developers who refuse to use these tools will be left behind, to their own detriment.

This framing is unfortunately detrimental in its own right.

While I'm not knocking anyone for having a highly optimistic view of where the technology will be in coming years, it is grotesquely inhumane to cast the holdouts as grumpy "get off my lawn" types.

Detractors (such as myself) are not the ones that are building systems that are actively harming other human beings. If anything, their fault is perhaps in caring too much!

Instead, we should be seeking ways to maintain solidarity, even in lieu of some of our fundamental disagreements.

Otherwise, we're ceding more and more control to the companies that want to pay the lowest-possible wages, offer the lowest-possible quality, and sell at the highest price they can name.

In that game, we're all losers. 🏆💩🏆